REVIEW: Threepenny Opera

The Threepenny Opera

directed by Scott Elliott

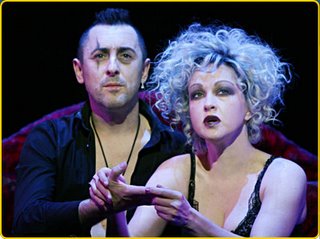

starring Alan Cumming and Cyndi Lauper translation by Wallace Shawn

Roundabout Theatre Company

at Studio 54

As I wrote after seeing a preview in April, I knew Scott Elliott's Threepenny Opera at the Roundabout was probably going to be received as some kind of disaster.

And so it has been. The reviews have been savage and Michael Riedel even reports the Tony nominators were embarrassed to have to fill out the Best Revival category with it. Yet I must stick to my guns and defend why I felt this production remains a worthwhile and sometimes rewarding "experiment" even if it violates some of the sacred tenets of Brechtianism and often of just good taste.

Let's be clear: Elliott's rethinking of Threepenny is a "queer"reading. Along with Isaac Mizrahi, he has repopulated it with leathermen, cross-dressers, and, in a particularly jarring finale, a scantily clad gold-lamee muscle-bound winged messenger. Mack's hideout is a club scene--obviously inspired by the very Studio 54 where the show is performed. The most questionable "adaptation" is casting Mack's mistress Lucy Brown with male countertenor Brian Charles Rooney, who plays the character quite clearly as a man in drag. (An interpolated "Crying Game" moment settles this.)

Visually this approach allows Elliott to deliberately jettison any old ideas of what we think Threepenny ought to look like--namely the Victorian trappings of Brecht's stipulated setting. I for one was glad to see someone disrupt this, especially since some revivals (I'm thinking of the 1989 one with Sting!) have drifted too easily into a Masterpiece Theatre nostalgia that inevitably serves up "culinary" delights to an American audience, no matter what the intention. So what we get from Elliott, Mizrahi and company is an intriguing post-punk milieu for the play, the inspiration clearly being the play's own Weimar Republic era, but with some updated decadence. You can't exactly say such a scene was unknown to Brecht, especially when you look at his early work, like the hedonist world of Baal. The minimalist neon settings (more outlines) by Derek McLane also may seem "anachronistic" yet cleverly conjure up in their elegant shorthand urban decadence--that of the old Times Square, really.

As I wrote after seeing a preview in April, I knew Scott Elliott's Threepenny Opera at the Roundabout was probably going to be received as some kind of disaster.

And so it has been. The reviews have been savage and Michael Riedel even reports the Tony nominators were embarrassed to have to fill out the Best Revival category with it. Yet I must stick to my guns and defend why I felt this production remains a worthwhile and sometimes rewarding "experiment" even if it violates some of the sacred tenets of Brechtianism and often of just good taste.

Let's be clear: Elliott's rethinking of Threepenny is a "queer"reading. Along with Isaac Mizrahi, he has repopulated it with leathermen, cross-dressers, and, in a particularly jarring finale, a scantily clad gold-lamee muscle-bound winged messenger. Mack's hideout is a club scene--obviously inspired by the very Studio 54 where the show is performed. The most questionable "adaptation" is casting Mack's mistress Lucy Brown with male countertenor Brian Charles Rooney, who plays the character quite clearly as a man in drag. (An interpolated "Crying Game" moment settles this.)

Visually this approach allows Elliott to deliberately jettison any old ideas of what we think Threepenny ought to look like--namely the Victorian trappings of Brecht's stipulated setting. I for one was glad to see someone disrupt this, especially since some revivals (I'm thinking of the 1989 one with Sting!) have drifted too easily into a Masterpiece Theatre nostalgia that inevitably serves up "culinary" delights to an American audience, no matter what the intention. So what we get from Elliott, Mizrahi and company is an intriguing post-punk milieu for the play, the inspiration clearly being the play's own Weimar Republic era, but with some updated decadence. You can't exactly say such a scene was unknown to Brecht, especially when you look at his early work, like the hedonist world of Baal. The minimalist neon settings (more outlines) by Derek McLane also may seem "anachronistic" yet cleverly conjure up in their elegant shorthand urban decadence--that of the old Times Square, really.

I'm surprised more attention (positive or negative) hasn't been given to Wallace Shawn's super-scatological translation. (And it is a translation, not a second hand free form "adaptation." Shawn reportedly knows German and started from scratch with the original.) I regret I can't recall lines in detail, and don't know the original text well enough to critique it intelligently, but I'll admit to bristling often at its vulgarity for the sake of vulgarity. We do need to be reminded of Brecht's "gutter Deutsche" to be sure, but is it overkill to interpolate obscenity into every line when Brecht didn't? Or is this necessary today to jolt us into the play's intended shock effects.

All this reinvention, though, downplays one crucial element of Threepenny: the, uh, politics. Not a small caveat to be sure. Elliott clearly intends to offend the audience and confront it with Brecht's unpleasant statements in blunt fashion. But is all the decadence on stage a little too cool? The beggars here come off as less poor than trendy. The great scene where Peachum schools one into how to panhandle has moments of audience awkwardness, when Elliott has his the actor, an African American, go into the posh front rows to beg and then tells the patrons to fuck themselves. But the fact the gym-toned beggar is clad in impeccable leather gear kind of dissipates the social meaning of the moment. The abstractness of the design scheme also deprives the "world" of its social deterministic context--in short, where's the poverty that Weill's anthems so powerfully sing of? And if the "message" of Threepenny is that capitalism makes thieves and beggars alike into shrewd businessmen in order to alleviate the poverty the system subjects them to... well that outer system isn't really dramatized here.

So the production ultimately fails at fulfilling the Brecht-Weill vision. But that doesn't mean it fails as theatre. It is best appreciated as a riff on Threepenny, then as any "definitive" staging. And some of the modern touches are quite effective: Jim Dale's cheap pastel-blue suit, capturing the idea of the cheap bourgeois businessman (Peachum) in modern terms; Tiger Brown as the archetypal "corrupt cop," replete with state-trooper sunglasses. I also thought the whole production is musically very strong--something gone uncommented upon in most reviews. The band, flanking the stage in the Studio 54 box seats, plays with power and whenever Elliott assembles his cast at the footlights to preach the Brecht-Weill gospel, it seems nothing can rob these songs of their polemical potency. (I also liked the original use of surtitles for certain songs like this--the effect was sometimes an ironic "bouncing ball sing along" effect, but it also aided the songs' "didactic" quality and made sure you heard Brecht's words!)

Cumming is definitely not your standard-issue Mack--but for lanky elegance and hetero charm he substitutes a compelling runtish outsider-ness that works for the character as a punk outcast. Cyndi Lauper, I felt, is the "find" in the show; her eerily quiet rendition of the "Ballad of Mack the Knife" makes for an entrancing beginning (who cares if there's no Brechtian "Streetsinger"). Someone should tell her, however, that the "Solomon Song" is not an eleven o'clock torch song, that Pirate Jenny doesn't care about Solomon et al, and that it's all a cynical lesson taught by an aging hooker, not a tearful lament. But who wants to spoil her fun, right?... As for the others, Dale and Ana Gasteyer make the Peachums as hatefully arriviste as their clothes, but the charm of Nellie McKay as Polly was lost on me, perhaps because her faux-ditziness came off as just ditziness from the balcony.

I'm glad to say I'm not alone in this dissenting opinion. Time Out's David Cote reviewing the show on TV for New York 1 rightly states it is "anything but dull" and that "there's no denying the production's theatrical gusto and visual excitement. In a Broadway scene almost entirely devoid of risks, this Threepenny dares to enrage, bewilder and offend." (Nice to have some cover on this, David!) This sums up my experience as well, "visually exciting," "bewildering," and infuriating as it sometimes truly was. I never doubted that there was adventurous interpretation going on, even when I completely "disagreed" with it. Sometimes "wrong" theatre is better than bad theatre.

I still maintain this production, if a failure (and it commercially isn't, btw), is some kind of noble failure. Unusual for Broadway--and for its greatest nonprofit player, the Roundabout--the failure, for once, is not in caving into commercial pressures or in watering down the text or in selling out to an untalented TV star. It's the kind of failure that I imagine is routine in the state institutional theatres of Europe--directors with bold concepts making messes of great plays. In other words, the kind of failures worth having, in that they signal a theatre that's alive and trying things, not one on autopilot.

Say what you like about this Threepenny. But it has a pulse.

CORRECTION: As you'll see in "Comments" here in this box, Mr. Lucy Brown himself has weighed in to set the record straight on both his vocal range (a "sopranista" not a countertenor) and Lucy's gender in the production (not drag but "pre-op transsexual"). Most interesting is his going on the record to clarify the concept behind the casting decision: "the point of making Lucy male was to introduce themes of homophobia, gay marriage."

7 comments:

Hi,

nice thoughtful review... interesting :)

I am not a countertenor though - the range and tone I sing those songs in is too high for a countertenor... I am a sopranista - or male soprano - who sings tenor (a darker tenor) but can also sing up through the soprano range... in what is believed to be the range and tone of the castrati :)

I am just pretty sensitive about that... it's like calling a Tenor a Baritone... a countertenor is like a mezzo soprano... a Sopranista is like a soprano... the songs might not sound too high, but that is because they sit in my range comfortably...

anyway, interesting thoughts :)

-Brian Charles Rooney

oh, sorry - one more thing... Lucy is not a drag queen - he is a transvestite (more a pre-op transsexual)... he is dramatic and humorous - but the point of making Lucy male was to introduce themes of homophobia, gay marriage, etc.

interesting review, playgoer. you've convinced me to give the show a look. (i previously had not intention of going.)

please keep reviewing as well. i look forward to more of your takes on things.

We saw Threepenny Opera when we were in NY earlier this month and mostly liked it. True, it wasn't a "traditional" performance, but can't a revival involve trying new things? I even liked the sets, which most of the reviewers criticized, so I won't attempt any more of a review than this, except to say that I did remark to my husband as we were leaving the theater that Threepenny with the politics left in wouldn't appeal to the crowd in attendance.

(I have, however, finally gotten hold of a copy of MNiRC and have read through it once. I think my worst fears have been confirmed, but will read through it again before commenting.)

A couple of observations: our theater excursion was the only time we saw people as old as we are. (At one dinner, the other people were so much younger than I am -- and I'm only 51 -- that I thought we were the chaparones.)

And second, the reason for this most likely revolves around the ticket prices. I don't know many young people -- at least those without trust funds -- who have the money to pay those kinds of prices more than a couple of times a year.

I'm young (mid twenties) and I hated the show.

1) It's poorly paced (this to me is Scott Eliott's main weakness as a director, and has been a recurring problem in every single one of his shows I've seen). Moments drag on too long for no reason, jokes don't lad because they're badly timed. Cindi Lauper takes 5 minutes to react to every line spoken before she speaks. I don't really think it has a pulse, Playgoer, I think it limps towards its conclusion.

2) Taking the class issues out of Threepenny is rather like taking the love out of Romeo and Juliet or the family dynamics out of Hamlet. It's not just a thing about the show. It is the fundamental backbone *of* the show. I think adding in the queer identity stuff could be really good if it was worked into an interpretation of the play that... um... understood it. In other words... if Threepenny has no class critique... what does it have? What do you create after stripping that out? In this case, the production team seemed determined to create something... well... cool and hip. That's hardly a replacement for the meaning taken out.

3) The play uses its politics to cheaply justify its crappy aesthetic by confusing dislike of the production with dislike of the production's themes. I didn't applaud the gay marriage lines not because I don't support gay marriage (I do. vehemently.) but rather because it felt like a cheap way to applaud a poorly done scene.

4) It's two best metatheatrical moments are stolen from better shows. The "rafts" that bring the characters on and off stage are stolen from the Mnouchkine show at Lincoln Center last summer and the English/German subtitled bit is ripped off of that bastion of edgy theater, "Thoroughly Modern Millie"

5) Alan Cumming's performance is intense... and wrong... it seems to have nothing to do with MacHeath at all, really, and everything to do with the MC from Cabaret, with the exception of that Tango song, which is quite nice.

6) I like the neon sign conceit, and I liked the kick line without music that went on just a little too long. If the rest of the play had had the clearness of vision and edge of those two things, the play would've been great. As it is its a muddled, muddy bore. And Jim Dale is a genius.

7) In other words, I don't think this play suffers from risk taking and o'erweening ambition. I think it suffers from shlocky cheap, poorly thought out decisions that don't work and a cast that has trouble making sense of those decisions.

I won't respond point for point to the previous counter-review, since I see the validity in much of what's said. I would just like to try to clarify two points of mine where I've admittedly left myself open to attack.

First, obviously one can't just say a production of Threepenny "gets the politics wrong BUT..." There is not "but" when it comes to Brecht. And I say that as a proud Brechtian myself.... Still, having said that and giving it an "F" for politics, as a lover of theatre I did find value in appreciating Elliott's work here on its terms, in exploring its own political/social/sexual politics agenda. It seemed a fresh rethinking, even if with this gaping whole at the center.

Second, I certainly did not mean to imply that this production is underappreciated because it's too edgy nor that its many critics just don't "get it." While I've often accused Broadway of neglecting work too out there, that's not the case here. (And ticket sales seem to suggest just the opposite.) Most of the critiques I've read I feel have great validity. I agree, for instance, about the pacing and the flat jokes--another offense to Brecht. Both Elliott and Shawn seem to approach them as one-liners, which Brecht didn't write.

For what it's worth, I also think it's such a distinctive production that will provide fodder for Brecht production historians for years to come!

So, without at all apologizing or eating my words, I fully fess up to mine being a "minority report" hopefully to be considered alongside the pans as just a different perspective.

To write, in a paranthetical aside at that, "who cares if there's no Brechtian "Streetsinger"," suggests that you, like Ben Brantley, understand zip about Brecht, Weill or this play. Brantley's largely negative review betrays as much patronizing ignorance re: brecht and brechtianism (a particularly ghastly coinage) as does your condescendingly positive notice. If you want to watch a smart director, intelligent actors, and a stupendous orchestrator completely reimagine (not just revive) a text, see SWEENEY TODD. Director John Doyle knows more about Brecht than these review writers, the cast, crew and director of THREEPENNY combined.

Post a Comment